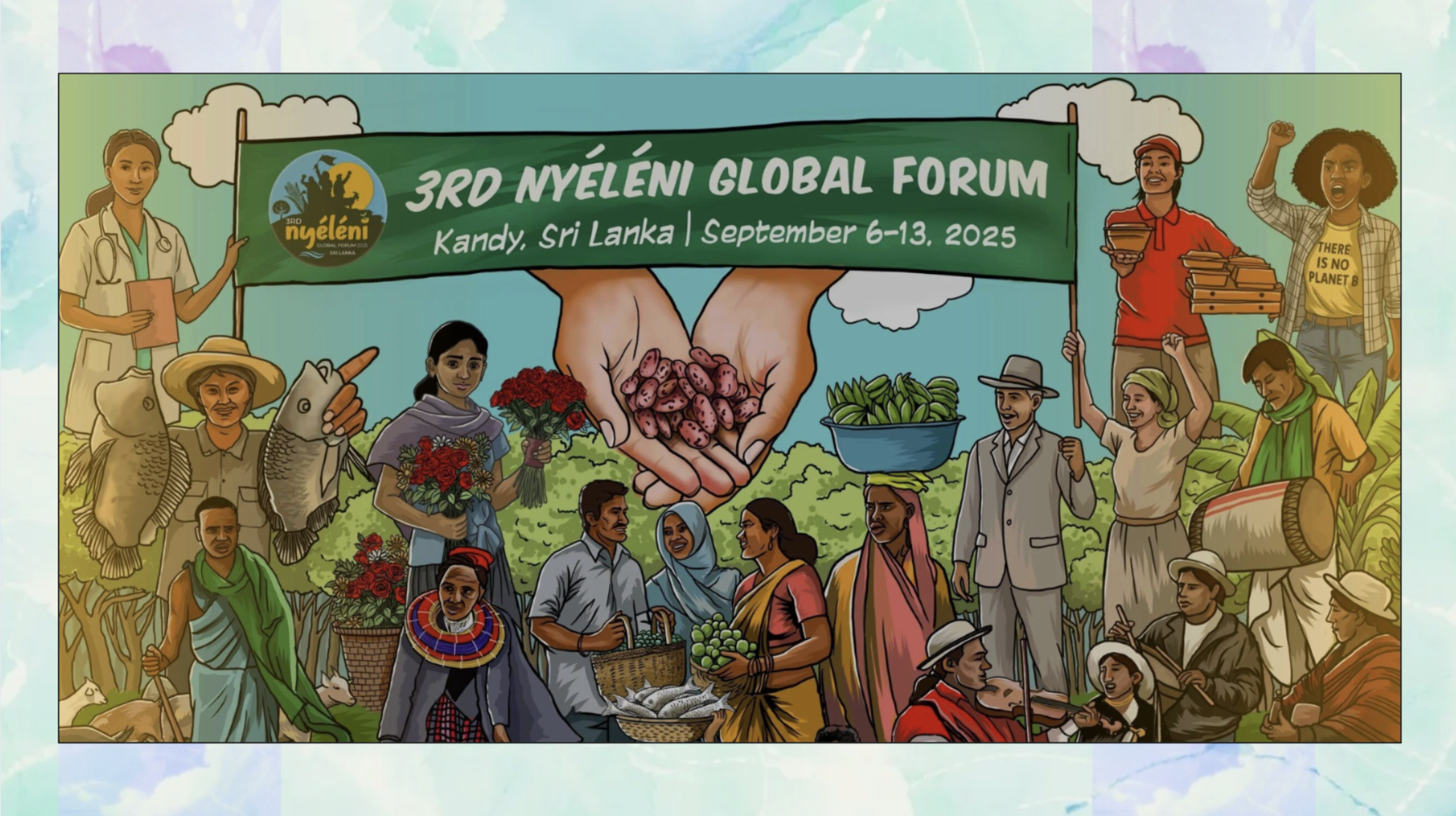

The third Nyéléni Global Forum that took place in Sri Lanka this past September was a landmark convergence for food sovereignty organizing – and for global social justice more broadly. Yet it nearly did not happen.

Despite representing a feat in movement building, the forum was delayed twice due to a lack of funding. It’s a common story – movements that have transformed global discourse and practice are still forced to scrape together the resources to gather, strategize, and lead.

Building upon years of accompaniment of the global food sovereignty movement since its inception, Grassroots International, together with our movement partners and allied funders and donors, has been taking a hard look at what is needed to sustain this vital movement.

A key shift, we argue, is to orient ourselves around the framework of solidarity philanthropy. This involves challenging the uneven power dynamics between philanthropy and social movements and forging deep relationships built on alignment, trust, and continuous learning, grounded in principles of solidarity and internationalism.

Solidarity philanthropy is particularly important to the food sovereignty movement, which aims to challenge existing power structures and build new relationships toward long-term visions of transformation.

Nyéléni: More than a forum

The third Nyéléni Global Forum in September brought together more than 700 people from 101 countries to advance the movement of food sovereignty. While next steps are still being synthesized, the energy and momentum coming out of it are palpable. Notably, a key output of the Forum – a Common Political Action Agenda – will be launched in November at the People’s Summit Toward COP30 in Brazil, representing direction and alignment for the food sovereignty movement.

These developments are only possible because of a decades-long movement-building process, of which Nyéléni has played a key role.

The food sovereignty movement was launched in the 1990s by peasant farmers under the banner of La Via Campesina to reclaim control of food systems from corporations and financial institutions. Soon after, the International Planning Committee (IPC) for Food Sovereignty was created as a coordination space for this rapidly growing movement.

As food sovereignty reached its 10-year mark, the IPC and allies organized the first Nyéléni forum in Mali in 2007, articulating a collective definition and framework for food sovereignty and broadening the movement to include feminist, Indigenous, environmental, and urban leadership. These and other movements held the second Nyéléni forum in 2015 to develop joint strategies to promote agroecology and defend it from cooptation at a moment in which it was increasingly gaining mainstream recognition.

By the third forum, the scope of Nyéléni extended well beyond food sovereignty, becoming a space for building cross-sectoral global resistance and transformative solutions. Notably, the latest forum was built upon an extensive regional consultation process, bringing the voices of countless more people into the forum than those physically present.

Over three decades, this food sovereignty movement has reshaped global food policy debates. It has influenced national and international law, from Mexico’s ban of GMO corn to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants. It has also inspired agroecology and land justice efforts worldwide.

Given the fact that this process has clearly demonstrated the type of grassroots organizing and broad-based participation espoused by progressive philanthropic institutions, the third Nyéléni Global Forum would seem like an obvious effort for them to get behind – but this was not the case. Why not?

Reimagining partnership and power

Here, we can identify a number of challenges within our sector that are important to grapple with.

One is a philanthropic landscape that is too often focused on fixing symptomatic problems instead of shifting the systems that create them. In food systems work, this shows up as funding dominated by paradigms of food security and food aid and seeped in the myth that hunger is simply a matter of quantitative production versus a matter of fundamental systemic change. For some, the concept of “sovereignty” may feel too political, as with the movement’s head-on opposition to an industry deeply tied to current corporate and market regimes.

Second, sector norms prize quick, quantifiable outputs that flatten complexity and undervalue the protagonism of the frontline communities that is possible through political education, base-building, and infrastructure. Even for those more open to food sovereignty, the long-term movement-building approach of the Nyéléni process does not easily lend itself to the type of outcomes that we often seek in a sector that over relies on metrics-based measurements of success.

A third challenge is limited global perspective and internationalist analysis within our sector that reinforces a false dichotomy of domestic vs. international, prioritizing the former. Global movement-building processes aimed at systems change are simply not on the radar of traditional philanthropy. For the food sovereignty movement, this lack of an internationalist perspective translates into chronic underfunding of the very cross-border organizing that makes its work effective. Fundamentally, having an internationalist perspective means challenging a global system predicated on the continuous extraction of natural resources and exploitation of labor from the Global South.

In light of these challenges, in the lead-up to the forum, the organizers of Nyéléni joined together with allied funders in a process of reflection, dialogue, and strategy, which Grassroots International was honored to facilitate. This included a special funder consultation in tandem with the regional consultations feeding into the forum and an active presence of funders at the forum itself. The movements involved stressed their goals of financial autonomy, asserting that without financial autonomy, there is no political autonomy.

As a contribution toward these goals, Grassroots International shared our recently launched framework of solidarity philanthropy with those at Nyéléni, who embraced it as an essential strategy in the pathway toward financial autonomy.

Four recommendations for advancing food sovereignty with solidarity philanthropy

What does this look like in practice?

As articulated in Solidarity Philanthropy: Redefining Philanthropy’s Relationship to Social Movements, Grassroots International identifies 10 key takeaways for transforming the sector. The four highlighted below are especially relevant when it comes to philanthropy more fully backing the food sovereignty movement and sustaining undersupported processes like Nyéléni.

1. Reckoning with our personal and institutional connection with wealth helps us to fundamentally reorient the work of philanthropy.

Understanding where our money has come from helps us understand where it needs to go. With this awareness and accountability, our financial resources can be a tool of solidarity rather than an obstacle.

If we are serious about engaging with social movements like the convenors of Nyéléni not in a grantor-grantee dynamic but in a way that uplifts their protagonism, we need to work together with them from a place of alignment in our understandings of how philanthropy both grew out of and feeds into multiple, interconnected systems of oppression. One example of many is understanding the links we may have to investment funds implicated in practices like land and water grabbing and divesting from harm wherever possible.

2. Grantmaking must be aligned with movement partners’ goals of financial autonomy.

This involves moving away from top-down, donor-driven project grants and onerous reporting requirements, toward long-term general operating or flexible core support and additional funding for movement infrastructure, learning exchanges, emergency response, and other needs as they emerge.

For a process like Nyéléni to thrive, the movements stewarding it need to be well functioning, and the extensive infrastructure needed to connect these movements across vastly different geographies and contexts, including periodic physical gatherings, is essential.

3. Accompanying social movements is a commitment to deep allyship beyond funding.

This involves cultivating our own political consciousness through open dialogue with social movements, ongoing political education, self-reflection, collective learning, and action to align with movements toward liberated futures.

This is why the presence of funders at Nyéléni this year – learning from and strategizing together with movements – was so significant. This is the result of years of work by social movements and movement support groups like Grassroots International and others to raise awareness of food sovereignty within philanthropy through efforts such as organizing educational sessions in funder forums and inviting global movement leaders to share their stories and exchange with participants directly.

4. We must organize ourselves.

Beyond our own giving, it is imperative that we organize our peers and collaborate with others in the sector to build a broader, more expansive and powerful constituency. Social movements are doing the painstaking work of organizing their bases in a hostile climate, and they need allies in philanthropy to organize themselves as well.

For food sovereignty, the Nyéléni Funders Circle, which we convened through the above-mentioned dialogues in the lead-up to the forum, is a concrete vehicle to grow a durable, aligned constituency capable of scaling flexible resources to match the movement’s long-term needs.

While the example of Nyéléni powerfully illustrates solidarity philanthropy at work, the framework is applicable across countless contexts, and we encourage those who are interested in learning more to engage with the framework. Through solidarity philanthropy, we can work to ensure that vital social movement processes like Nyéléni, the COP30 People’s Summit, and many others are not just scraping by but have the financial autonomy needed to thrive – and to put their transformative visions that the world so urgently needs into reality.

Chung-Wha Hong is Co-Executive Director of Grassroots International.

Saulo Araujo is Director of Global Philanthropy of Grassroots International.

%20(1280%20x%20720%20px)%20(44)%20(1).png)

%20(1280%20x%20720%20px)%20(34).webp)

.webp)

%20(1280%20x%20720%20px)%20(37).png)

.webp)