Agroecology means many things to many people. That’s part of its strength – and part of the reason it’s often misunderstood.

At its core, agroecology is about how food is grown, how land is governed, and how ecosystems are cared for. Sometimes described as “farming with nature”, it includes a wide range of principles and practices: seed saving, soil regeneration, agroforestry, rotational grazing. But it’s more than a set of techniques.

Agroecology is also fundamentally a political project – rooted in Indigenous and smallholder farmer knowledge systems, and grounded in struggles for food sovereignty, land rights, and community self-determination.

To understand agroecology, it helps to start with the people doing the work.

In South India, farmer-led cooperatives are helping growers move beyond monocropping and plant up to ten vegetable varieties an acre. In East Africa, pastoralist communities are sharing knowledge on land restoration and drought resilience. In Latin America, quilombola and Indigenous groups are restoring forests through agroforestry and community land stewardship.

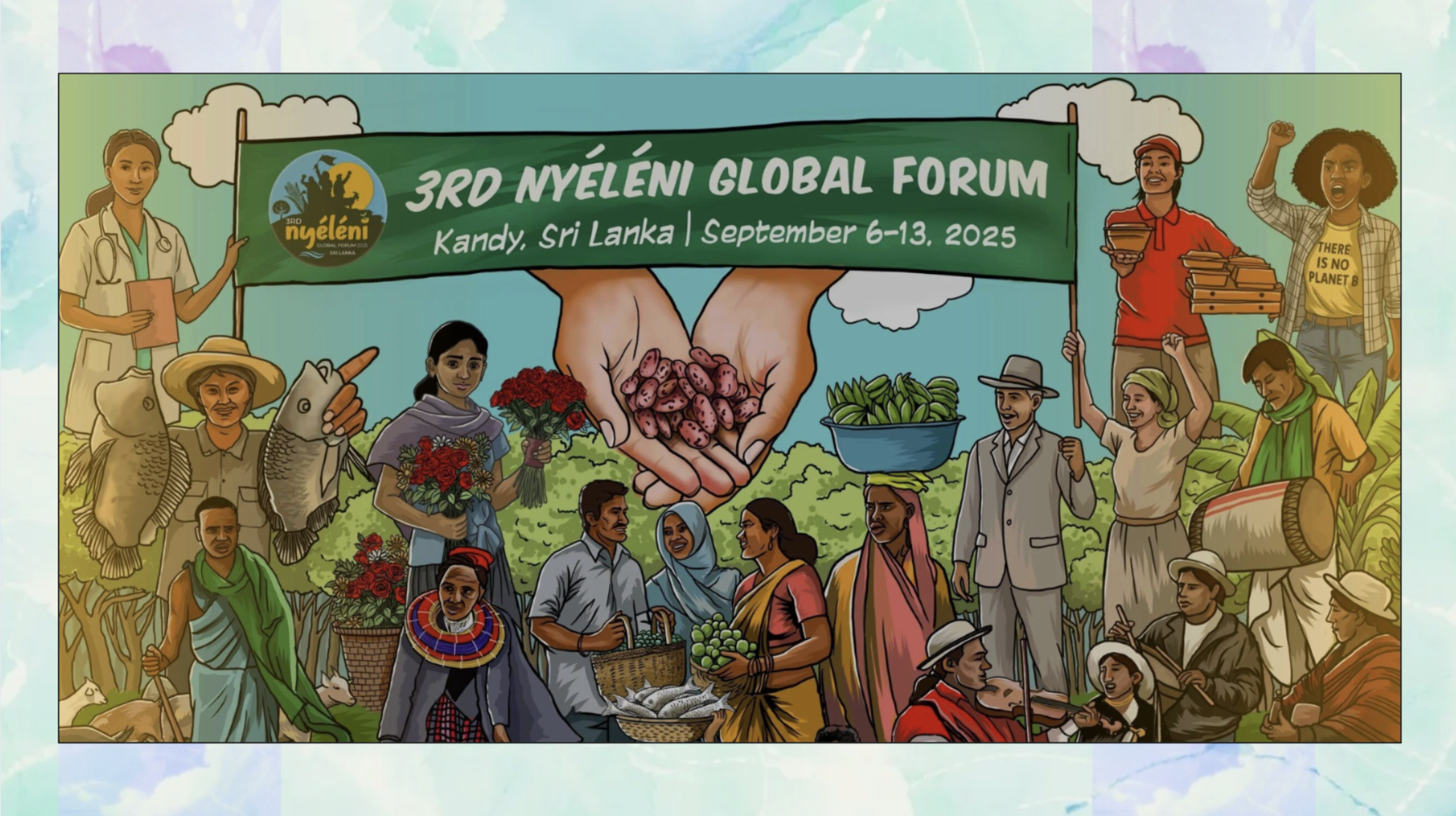

We can also look at how social movements have defined the term. The term was first popularized in the ‘90s by the global peasant movement La Via Campesina. In 2007, more than 500 peasant, Indigenous and family farmer organizations gathered to launch the Nyéléni process, an ongoing dialogue to articulate a shared vision of food sovereignty.

That led to the 2015 Declaration of the International Forum for Agroecology, which framed agroecology as both a practice and a political commitment: grounded in shared knowledge, rooted in place, and led by food producers.

An evolving landscape of agroecology funding

Today, agroecology is gaining traction in institutional philanthropy and global development.

At COP 28 in 2023, two dozen leading philanthropies called for a tenfold increase in agroecological and regenerative agriculture funding. In Switzerland, more than half of agricultural development projects in a recent analysis had an agroecological component. And networks like FORA, SAFSF, and GAFF are convening conversations about how to move funding more equitably – and with greater proximity to the people doing the work.

That’s what this series is about. Over the coming weeks, we’ll feature stories, interviews, and commentary that explore the intersection of agroecology and philanthropy. We’ll look at the role of local funds, the challenges of intermediary pipelines, and the question of what it means to fund agroecology in a way that reflects its values.

Agroecology is widely understood to have 13 principles, one of which is the co-creation of knowledge. We’re interested in how much co-creation is happening in the agroecology space; where funding meets practice, and how systems change happens – or doesn’t.

Agroecology may be nuanced and locally adaptive, but it’s not abstract. It lives in seeds, in soil, and in the hands of people defending their land. That’s where we’ll start.

%20(1280%20x%20720%20px)%20(34).webp)

%20(1280%20x%20720%20px)%20(44)%20(1).png)

%20(1280%20x%20720%20px)%20(37).png)

.webp)

.webp)