As funders wrestle with how to get capital flowing more directly to communities, the Fondo Territorial Mesoamericano offers a reminder: the infrastructure is already there.

The fund was spun up in 2021 by a standing coalition of territorial organizations called the Mesoamerican Alliance of Peoples and Forests. Territorial organizations are Indigenous bodies that exercise ancestral authority over land and resources; in Mesoamerica, Indigenous communities have a historical claim to over 50 million hectares of forest.

The Alliance was formed in 2010 to bring together ten territorial groups – like the Miskito Indigenous Peoples Organizations in Honduras and the Association of Peten Forest Communities in Guatemala – to manage forest concessions, influence policy and protect Indigenous rights.

Built and governed by territorial organizations, the fund moves resources to seven countries in Mesoamerica through this existing collective body. In other words, the fund emerged from an existing base of power – an alliance of actors already engaged in advocacy, land defense, and conservation.

That makes it different from many new philanthropic experiments in local grantmaking – and it allows the fund to move money directly to frontline and grassroots organizations, for agroecology and other purposes, with fewer transaction costs and deeper context.

We spoke with María Pía Hernandez, a lawyer specializing in international environmental law who serves as the fund’s regional manager. We talked about the fund’s origins, the mechanics of grantmaking, and the broader political and ecological context in which they operate.

How did the Mesoamerican Territorial Fund come to be?

The fund exists because this political platform started positioning and fundraising to support grassroots organizations in these areas — both for forest conservation and territorial rights. Those were the two main areas: how to conserve the forest in a sustainable way, and how to strengthen the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities, particularly in the face of extractive industry expansion, agriculture frontiers, and the criminalization of environmental defenders.

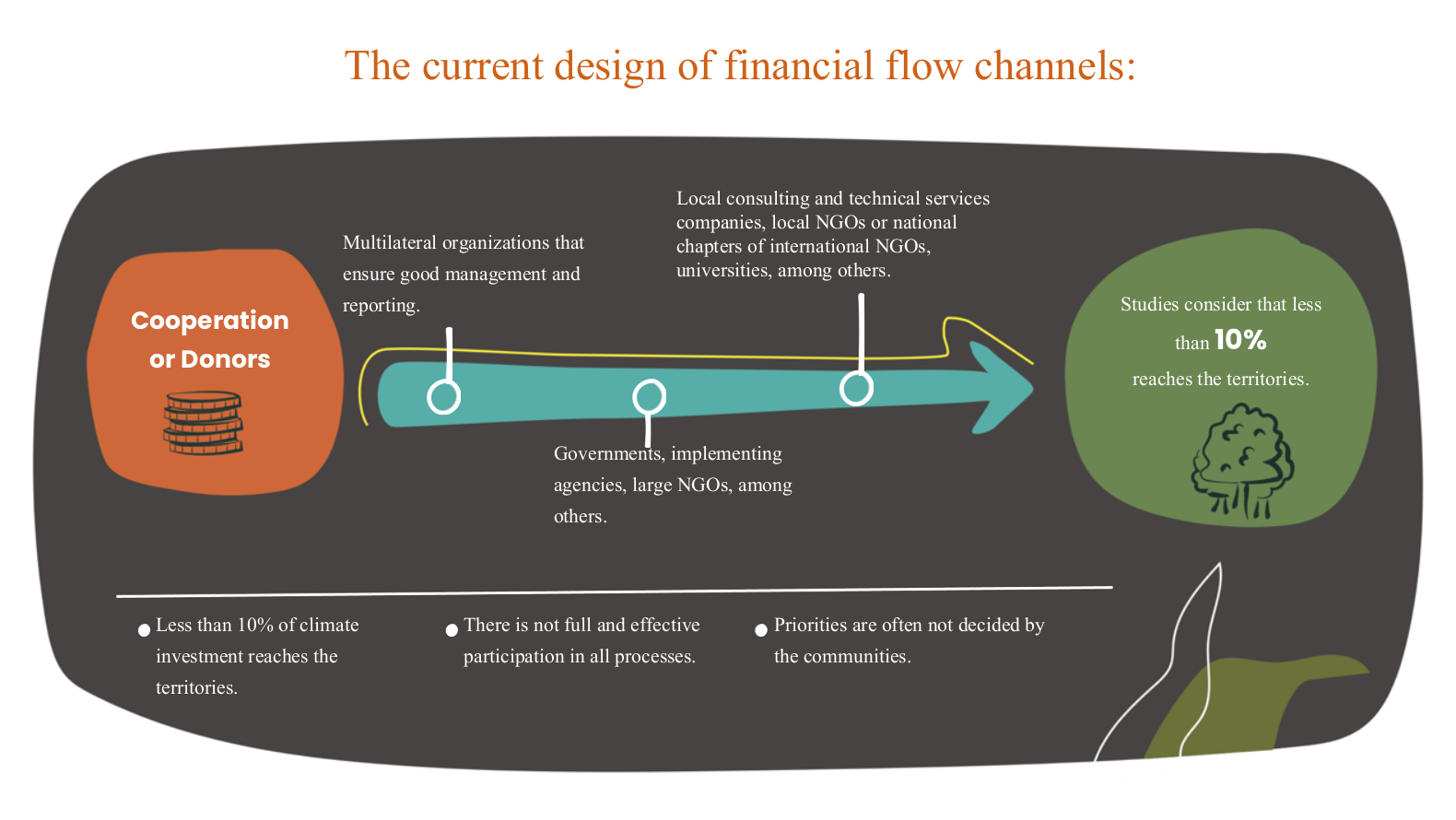

These organizations either own a huge amount of forest because of ancestral collective land titles, or they manage forests through concessions. They created and designed the Mesoamerican Fund as a financial mechanism to channel funding more directly — with fewer transaction costs. Sometimes, only 10% of the money actually reaches the organizations it's meant to support.

Where is the rest of the money going?

We’ve investigated this. You hear about billions of dollars going through the Global Environment Facility, the Green Climate Fund, bilateral cooperation — and it’s supposed to support Indigenous populations and local communities, to fund local solutions for climate change and biodiversity conservation. But when you go to the ground, you don’t see the money there.

There are many intermediaries: big NGOs, governments, a lot of bureaucracy. And the funding that arrives is often inflexible and inaccessible. Most of it stays within that chain. I’m not saying I’m against intermediaries or big organizations. But the fact is, they are often far from the needs of the territories — and they don’t channel it properly.

What does agroecology mean in the context of your work?

Indigenous peoples and local communities have been practicing agroecology since forever. They don’t call it that — the term is new. But it refers to a way of cultivating land, producing food with less contamination, fewer chemicals, and in line with traditional practices.

The Mesoamerican Territorial Fund doesn't only support agroecology, but we fund conservation and promotion of traditional,production, ancestral knowledge, and endemic species. And a lot of that is carried out by women.

Most of the funding we provide for this work goes to Indigenous and local women. They are the main ones practicing agroecology — using their land to feed their families, cultivating medicinal plants, and sustaining their communities.

What does the grantmaking process look like?

We’ve been functioning as a fund for three years. Most of our early support came from philanthropic actors — the Climate and Land Use Alliance, Ford Foundation, and others. Now we’re trying to diversify — including applying for bilateral cooperation funds. That’s more bureaucratic, but it can be more predictable and sustainable.

When we apply for funding, we start by consulting with our grassroots networks about what issues they want to work on. So when we submit a proposal, it's not something we invented at our desks. It’s been consulted already.

Once we receive the funds, we open a call for proposals. We prioritize our members, but also want to support other organizations with strong records. Our selection committee includes five people — some internal, some independent — and we help applicants formulate their proposals. Many of these groups are excellent at what they do, but they’re not professional grantwriters.

Once projects are approved, we don’t just send the money and walk away. We accompany the implementation — supporting them throughout the process.

You’ve also built in a complaint mechanism. Can you talk about that?

We believe we’re trying to do good. But doing good doesn’t always mean we get it right.

It’s possible to fund a project with good intentions, but that ends up causing harm — for example, if a building project in a protected area causes ecological damage. That’s why we created a complaint form. Anyone can contact us if there’s a problem: if a project is causing harm, or if there's misconduct like harassment.

These things happen everywhere. Being an Indigenous-led fund doesn’t mean we’re immune. Accountability is part of our job.

What makes your fund different from others working in this space?

We’re regional. Most other funds operate in one country. We cover seven — from Mexico to Panama — and we’re rooted in a regional network with strong local presence.

Some other funds work exclusively with Indigenous peoples. We work with Indigenous and local communities. Our scale and structure is rooted in these grassroots and territorial organizations. The idea is not only to support Indigenous people and local community organizations to access funding, but also to accompany them to enhance organizational capacities and sustainability. As a lived experience led fund, Fondo Territorial Mesoamericano seeks to enhance territorial governance.

.webp)

%20(1280%20x%20720%20px)%20(44)%20(1).png)

%20(1280%20x%20720%20px)%20(37).png)

.webp)

%20(1280%20x%20720%20px)%20(34).webp)