This story is part of a series created with Our Collective Practice and the Girls' Power Learning Institute

What does it mean to ask a Dalit girl to dream?

To invite her to imagine joy, power, and possibility in a world that has consistently denied her even safety? To encourage her to draw a future when her present is still shaped by violence, exclusion, and silence?

When I walked into the dreaming workshop, I was not afraid of the girls’ capacity to dream, as I have seen their brilliance blaze through impossible odds. What unsettled me was the weight of the invitation. In a society that has punished Dalit girls for simply existing, was it fair to ask them to imagine a world where they could fly?

And yet, they did. Fiercely. Tenderly. Politically.

In the beginning, the silences were heavy. I asked the girls, “What does your dream world look like?” They paused, not because they had nothing to say, but because no one had ever asked them this before. Dreaming is a privilege often denied to girls who are taught that survival is enough. For Dalit girls, raised within the tight grip of caste, patriarchy, and intergenerational poverty, imagining a world that honours their dignity is radical.

But they took the invitation seriously. And slowly, beautifully, the space began to swell with colours, stories, and visions.

Navanitha imagined a village where trans girls and women are safe, respected, and whole. Her world was not utopic because it had no conflict; it was utopic because it had care, inclusion, and the safety to be oneself.

Agalya spoke of a magical artifact that could harness the world’s happiness and sorrow without harm. She imagined a pen, simple and unassuming, that could only write the truth, but when held with kindness. With it, she said, stories of pain would be told with dignity, and stories of joy would be shared without pride. In that moment, Agalya demonstrated that even young girls carry the weight of ethics: they want to change the world gently, justly, and with care.

What happens when girls dream?

They build what the world refuses them. Their visions challenge dominant ways of knowing and being, pushing back against epistemic erasure. In naming what care looks like, what power could mean, and who gets to lead, they are producing feminist knowledge rooted in lived experience, defiance, and collective imagination.

I watched Mercy draw herself as a president, governing with fairness. Sumithra imagined herself as an elder, offering intergenerational wisdom to a community held together by trees. What was fascinating to me is how they did not mimic the oppressive leadership they have seen, but rather they reimagined leadership rooted in justice, joy, and care. These were not childish fantasies. These were sharp political visions.

And perhaps the most striking thing, something that humbled me deeply, was the joy that filled their worlds. Vidya, who imagined herself as a clown, chose to spread laughter as her act of resistance. In a world that wants Dalit girls to be quiet, small, and invisible, choosing joy is a revolutionary act. Yameema’s world of magical butterflies was light and radiant and that lightness itself was political. I often forget how heavy we adults can become in our resistance. These girls reminded me that laughter can be a strategy, and dreaming is a method of surviving and reshaping.

It was in this context that I was reminded of a powerful quote by Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, the visionary Dalit leader and architect of the Indian Constitution: “Cultivation of mind should be the ultimate aim of human existence.”

To cultivate the mind is to liberate the imagination and for Dalit girls, whose lives are hemmed in by oppression; cultivating the imagination is a form of refusal. In dreaming, they step beyond the limits that caste society has drawn around them. It is an act of defiance, a declaration that they will not stay confined to the place society has assigned them.

This is what dreaming does. It chips away at the internalized beliefs of “I am not meant to lead” or “I am not meant to thrive.” Dreaming interrupts generational scripts of marginalization. And as adults, especially those of us from the Dalit community, it shifts us too. It shook me. It demanded that I make more space, soften my control, and surrender to the brilliance of their visions.

What did I learn about their world-building? Their sense of care is expansive. Kavya spoke of animals and humans sharing power. Her dream carried a lesson for all of us about coexistence and ecological balance. In a world that extracts, they imagine relationships. Where we see collapse, they imagine regeneration. The girls hold so much wisdom.

It also made me ask difficult questions about the spaces I hold and the funding ecosystems we navigate. If dreaming is political, creative, and feminist, then why do so few donors prioritise it? Why do metrics and logframes still dominate, when what we need are spaces for reflection and radical reimaging? These girls taught me that dreaming is not “just storytelling,” it is strategy. It is survival. It is system change seeded in spirit.

If donors truly believed in shifting power, they would fund dreaming as rigorously as they fund outputs. They would trust girl- and youth-led organisations not because they tick a box, but because they are seeding transformative futures. These dreams are blueprints for justice.

One girl said to me, “If I can imagine this world, maybe I can start building it.” That sentence stayed with me. I believe the role of facilitators, activists, and feminist practitioners is not just to bring resources or develop frameworks, but to remind girls that their imaginations are legitimate sites of resistance.

In this space, world-building means asking: What if joy was not an afterthought? What if care was the organising principle? What if power was shared, not hoarded or gatekept?

And so I left that space full, broken open, but full.

As a Dalit feminist, I know how systems conspire to steal our dreams. But I also know that dreams, once articulated into visions, can become movements and drive systems to change. The girls I walked alongside in this process are already leading us there, we just need to listen.

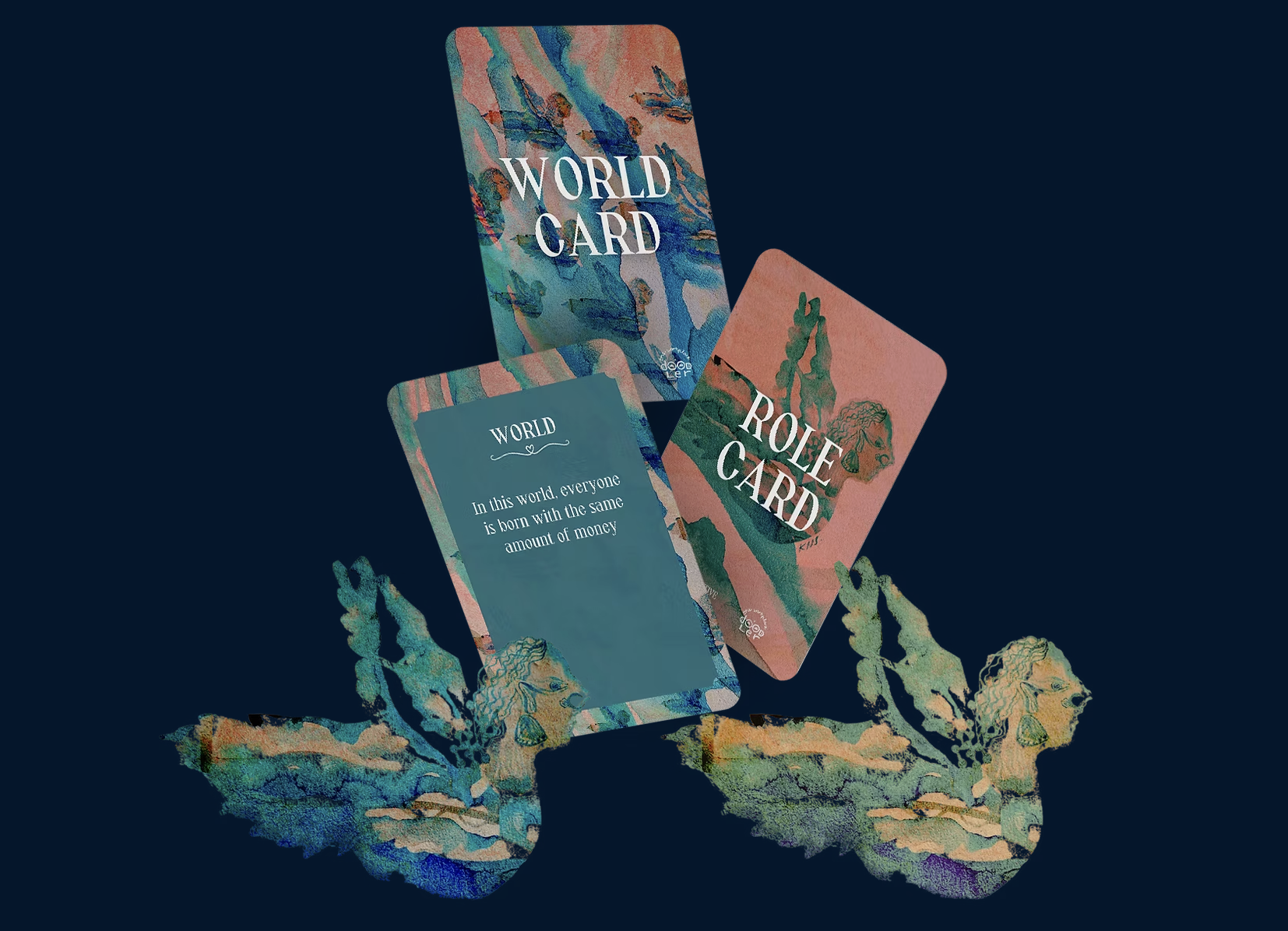

The Dreaming & Worldbuilding Game is a portal into worlds you can collectively create, weaving the past, present, and future. Inspired and seeded by and with girls and young feminists, this game is grounded in the foundational principles and tactics underpinning girls’ and young feminists’ resistance, power, and dreams. Click here to learn more and download the game!

.webp)

.webp)

%20(1280%20x%20720%20px)%20(41)%202.webp)

%20(1280%20x%20720%20px)%20(38).webp)

%20(1280%20x%20720%20px)%20(31).png)

%20(1280%20x%20720%20px).webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.gif)

.webp)

.gif)